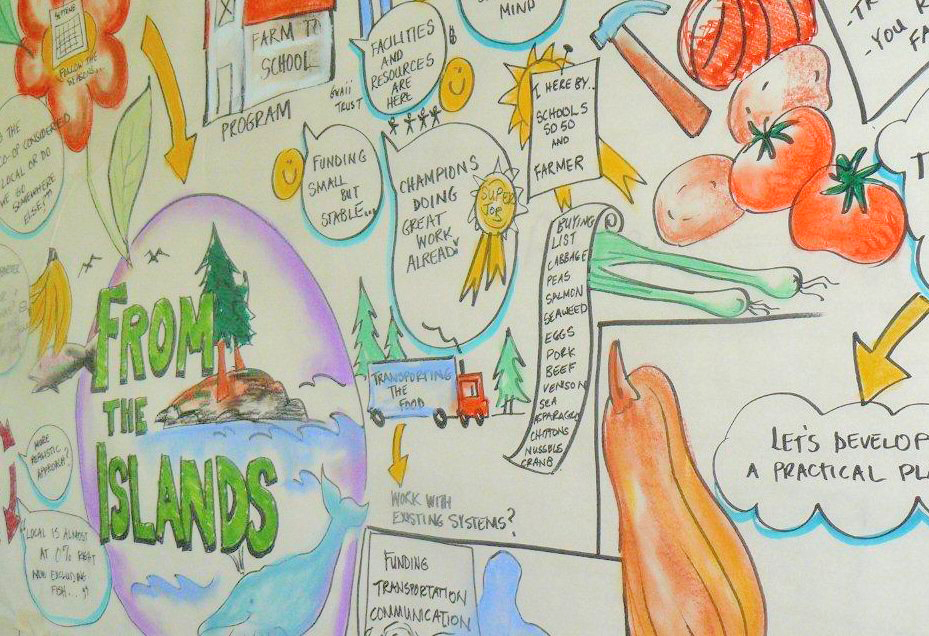

Photo Above: A mural depicting the vision of the first Learning Lab on Haida Gwaii. Photo by Kiku Dhanwant.

Haida Gwaii, an archipelago of islands on the north coast of British Columbia is home to fewer than 5,000 people (most of whom live on one of two main islands) and an abundance of local food resources. People hunt deer, raise scallops, catch wild salmon and forage for mushrooms. During the summer months, there are four farmers’ markets to serve local residents.

How to best connect these resources with Haida Gwaii’s cafeterias? That was a key question at a recent community visioning session. On May 16, people representing 16 different groups – including farmers, principals, teachers, food coordinators and cooks – gathered in the town of Port Clement to dream up a vision of school food in Haida Gwaii. Their grand vision was summed up this way: ‘From the Islands.’

It reflects the fact that lifestyles here revolve around foraging, hunting, fishing and growing food, says local Farm to School coordinator Kiku Dhanwant. The local harvest is a “very important part of the ancient and the current culture,” says Dhanwant. “So we need to cultivate a culture of realizing where our food comes from, and being a part of gathering it.”

The May gathering was the first of three to four Learning Labs that will take place over the next year to move this vision forward. The Learning Lab process was launched in early 2014 as part of a national Nourishing School Communities Initiative, led by the Heart and Stroke Foundation and funded by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) and with Farm to Cafeteria Canada as a key partner providing leadership and channelling funds to communities like Haida Gwaii to scale up their Farm to School activity.

There is lot of interest on the islands, says Amber Cowie, who started the Learning Lab process before Dhanwant took over as coordinator. Funding from the provincial Produce Availability Initiative in 2010 helped launch relationships between three farms and eight public institutions, including one hospital and seven schools.

The Learning Lab process is designed to scale up a particular activity within a community. First, a community of practice is convened to articulate their vision and broad goals, and come to a consensus on the immediate next steps.

The group comes together at six month intervals to review progress and revise the action plan. Each session ends with another set of priority action items.

The idea came from a non-profit in the US called School Food FOCUS, which originally developed the program to scale up efforts to procure more local food for student meal programs within larger — over 40,000 student — school districts.

This is the first attempt to bring the Learning Lab process to a remote aboriginal community in Canada. Dhanwant says it’s a really good fit for Haida Gwaii, a tight-knit community that is blessed with tremendously rich local food resources.

Right now, CPAC funds are supporting Dhanwant’s position and the costs of running the Learning Labs. “Just having this position, regardless of whether it’s me or somebody else is really critical,” says Dhanwant. “Somebody who can just focus on what the needs are and connect them. Everybody is maxed in their positions.”

Six of the schools in the region have food coordinator positions funded (by CommunityLINK, via the school board) for about four hours per week. The Gwaii Trust, a local economic development fund, contributes $85,000 per year for schools to purchase food.

In terms of producers and suppliers, there are at least four local meat processors, three fish and seafood processors, and other individuals who raise scallops and oysters. Dhanwant is aware of 15 to 20 farmers, some of whom are quite small.

She says she hopes to supplement the schools food budgets to be able to purchase more locally. Meat is particularly expensive because animal feed is so costly to ship in. But farmers are keen to be involved, says Dhanwant. “We get a lot of daylight here, I know that farmers are really wanting to extend their growing season. There is a lot we can put away from the farms. I’m focused on building capacity for preserving foods, promoting the idea of a pantry because we live in a northern climate.”

The fact that local is more expensive is challenging, says Vicki Ives, principal at Sk’aadgaa Naay Elementary School. “We do have a limited budget at the school,” she says. Money for staffing is tight, too; she says she would love to hire another staff member for the kitchen, which currently has one cook who works 20 hours per week but is able to get volunteers to help do food preparation. “It would be nice to be able to give them a bit of a stipend, too,” says Ives. “They’re dedicated.”

So too are the Farm to Cafeteria coordinators and its director, Joanne Bays, says Ives. “They are really willing to help us,” she says, “and without them it wouldn’t be getting done.”

![]() 2014 1st Learning Lab Newsletter for Haida Gwaii

2014 1st Learning Lab Newsletter for Haida Gwaii

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Farm to Cafeteria Canada.